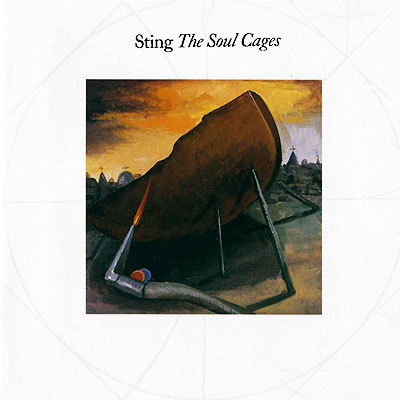

The Soul Cages

Soundbites

"My father died in 1989. We'd had a difficult relationship, and his death hit me harder than I'd imagined possible. I felt emotionally and creatively paralysed, isolated, and unable to mourn. I just felt numb and empty, as if the joy had been leached out of my life. Eventually I talked myself into going back to work, and this sombre collection of songs was the result. I became obsessed with my hometown and its history, images of boats and the sea, and my childhood in the shadow of the shipyards."

Sting, 'Lyrics', 10/07

"The theme of the album is essentially about dealing with death. For me, at my age, it's an important subject. I don't kid myself that my experience is unique but I have a way of expressing things through songs that may be useful to someone else some sort of therapy. They're still rather overwhelming for me."

Sting, The Advertiser (Australia), 2/91

"I'd reached the age of thirty-eight, and I wanted to assess my life; figure out what had gone wrong, what had gone right. I started at the beginning; I started with my first memory. As soon as I remembered the first memory of my life, everything started to flow. The first memory was of a ship, because I lived next to a shipyard when I was young, It was a very powerful image of this huge ship towering above the house. Tapping into that was a godsend. I began with that, and the album just flowed. It was written in about three or four weeks. Having written all these words in a big burst, I then fitted them in with the musical fragments I had and put it together. I'm fairly pleased with the record. I think it achieved what I wanted it to achieve in that I feel somehow, I don't know, like I've done the right thing."

Sting, Rolling Stone, 2/91

"That's what the 'Soul Cages' is about in a way; working through things yourself rather than trusting in mass ideologies. We come into the world alone and we leave alone. I mean, I'm not anti-religious, but if you believe anything wholesale, you open yourself up to a lot of perversions of the initial content. That's unhealthy. The core ideas behind ideologies are great, but invariably they get twisted. I'm not an expert, I'm just working on myself. That's the path to choose".

Sting, Creem, 2/91

"This latest album has got the best reviews I've ever had - and the worst. There's a polarity about them which is quite extraordinary and, I suppose, in a way, confirming. Some of the reviews you can classify as revenge of the nerds - hate mail. A lot of it, you're touching deep areas of resistance and prejudice and, actually, hatred, which I don't know how much is to do with the music or to do with my projected image, or what."

Sting, The Independent, 2/91

"Most people who listened to the new album said they didn't like it the first time, but it grew on them. It's much more layered than my stuff used to be. I think my intention is to implicate the listener, rather than impress him immediately. You'd be surprised that the basis of 'All This Time' the most recent single is actually a piece of Bach - really pretentious, but it's true. The way the chorus comes in is lifted from the first cello suite. And the lyrics I wrote in Normandy. I went to Normandy one weekend when I'd just started the album and I stayed in the hotel that Proust used to stay in. So I got his room: OK, I'm in Proust's room, Remembrance of Things Past and all that, right, sat down and looked at the sea. Wrote a few images down, a bit of free association, and then after a while you get some idea of a structure. Songwriting has always been a miraculous process which is incredibly satisfying, and I don't necessarily understand how it's done. And, for me, it happens with less and less frequency, actually. Which is scary, I suppose."

Sting, The Independent, 2/91

"It's still difficult for me to sit down and listen to the album properly, because I start to break down. When a song really works it can be very emotional when you sing it. You don't know whether to sing or to cry - it's an odd feeling. My music is the only way I have of really getting in touch with my deep feelings, because I suppress them. There was nothing else I could have written about on this record. So to me, it's not a brave record. I know there would be this record or there would be no record. But I do feel better about my father, and much looser in general than I've ever been."

Sting, Bass Player, 4/92

"Actually I think of it as my best work. All my albums sell about five or six million copies, so 'The Soul Cages' wasn't exactly a flop. But it was attacked most in England for being pretentious. The buzzword was gloomy, I think, or depressing. Maybe I'm defensive about it, but it's very heartfelt, very earnest. I couldn't get away from these ideas about my background, my father, death. I had to get them out of the way, almost as part of the mourning process, so I could then get on with writing songs for fun. Which is what I did on 'Ten Summoner's Tales', which people seemed to like much better. But that's fine. A whole body of work should reflect lots of different moods, and that was a very dark period of my life. If I was to be honest, I would have to make a very dark record."

Sting, Mojo, 2/95

"There's a polarity of feeling about that record. It was roundly panned by the critics, but some people got it: The recently bereaved write to me about it. There's always a market. Small, but steady. People say, My brother died, or, My parents died, and the record helped me."

Sting, Q, 5/96

"I grew up in Newcastle, a shipbuilding center, and as a boy I read "Treasure Island." The title song is based on a fable about souls trapped under the sea in Davy Jones' locker and how a sailor wagers the king of the sea to free them. 'The Soul Cages' was an album of mourning. When you lose both your parents, your realise you're an orphan. Sadness is a good thing, too, to feel a loss so deeply. You mustn't let people insist on cheering you up. I'm very proud of that album."

Sting, Billboard, 9/99

"I was 38, halfway house if you like. What I turned to was my earliest memory. The shipyard. There was always a huge ship towering above the houses at the end of Gerald Street in Wallsend where I grew up. As soon as I got that down the thing was written in two or three weeks. It poured out. Although it was painful, it wrote itself almost, free-associating. I only realised what it was about as I went along. The journey back to where I came from. The idea of death. Lines about this father thing kept coming up. Something was saying I had to deal with it."

Sting, Q, '91

"I'm not sure I want to go through singing this album night after night on tour. But I have to of course, and it serves a purpose. Even though death isn't much of a party subject it's valuable to me to think about it."

Sting, Q, 2/91

"Having lived and spent a lot of time with these so-called primitive people (The Indians) I realised that death is something that is obviously important to them, because they mourn. I figured that I'd have to go through some sort of process where I would get this stuff out. Once I'd worked that out, I realised that I was going to have to write a record about death. I didn't really want to."

Sting, Rolling Stone, 2/91

"I don't really think that people know what to expect from me now. I don't think the 'Soul Cages' is going to conform to any of their expectations - I think they're expecting a record about ecology or something. If they're surprised, then I'm pleased. And the next record will hopefully surprise them again."

Sting, Rolling Stone, 2/91

"I was trying to suggest where I came from, so I took out any Afro-Caribbean or other world influences on the record. I enjoy that music, and I like making it, but it didn't seem to apply. So the bulk of the record is based on Celtic folk melodies."

Sting, St Paul Pioneer Press, 8/91

"For almost three years, I hadn't written even one rhyming couplet. I'd written a lot of little fragments of music, but there were no real ideas coming out. I was genuinely frightened. At one point I thought, "This is it, I've just dried up !" Then I started to wonder why my creativity would suddenly dry up. Perhaps I was afraid of what might come out if I wrote something. I think there was an awful lot of denial and blockage going on in my subconscious - there were things I wasn't ready to face. This went on until after I'd gotten a band together and had two months before the whole process [of rehearsing and recording] was supposed to begin. I still didn't have a damn word. I spoke to Bruce Springsteen about it. He was just starting his own album, and I said, "Bruce, I don't know what to do. Have you got any bad songs you don't want" He offered me a couple. Then one day I just sat at the piano and started to free associate, mumbling to myself there was nobody in the house - and the mumbling got louder and gradually I started to sing lines. Words started to flow out 'Island of Souls' was one of the first. So I wrote down what I thought were just disconnected images and lines. Quite a few were about the sea, and all were linked somehow to my father and his death. Suddenly, I realised I was mourning my father, and then the whole thing poured out of me like a river - which became the central image on 'All This Time'."

Sting, Bass Player, 4/92

"I think a lot of ghosts were exorcised 'The Soul Cages', which was dedicated to the memory of his late father. That album was very personal, confessional, and therapeutic in terms of facing death and loss. But I guess you could say the therapy worked, because now I have a new sense of freedom, a desire to move on and make songs solely intended as entertainments, designed to amuse."

Sting, Billboard, 2/93

"Still my best work."

Sting, Arena, 1/94

Backgrounder

Review from Q magazine by Peter Kane

Some words of warning to all would-be millionaire rock stars: the job isn't always what it's cracked up to be. Whether you're the man of the people Phil Collins type, a hermetically sealed George Michael or another ageing juvenile Rod Stewart in the making, there comes a time when you have to stop trying to make it in films, put an end to scouring the globe in search of painless diversion or using your name to sway public opinion and get back to making records. Being handsome and/or famous is little help in the creative process and sometimes, despite the perks, the pressure of expectation begins to bite. Sometimes it even hurts; especially if you used to be called Gordon Sumner, came from sound blue collar stock and have trouble reconciling your natural, decent, liberal instincts with the excessive rewards of your chosen career.

It's been a good three years since '...Nothing Like The Sun' and 'The Soul Cages' accompanying press release, penned tellingly by the man himself, ranks much of the writer's block suffered during that fallow period when he still managed to take on the guise of Great White Protector Of The Rain Forests. His muse must have been merely puffing her feet up, though, for he's gouged out of himself another most Sting-like affair: a panoramic sweep of the soul that is fastidiously mounted, overtly literate and, against the odds even occasionally quite moving, not least on the fragile closing ballad 'When The Angels Fall' or 'Why Should I Cry For You's' elegantly simple melody set against a looping Third World beat.

'Island Of Souls' with its droning piped intro, swoosh of strings and fluttering acoustic guitar establishes the mood of the piece with a misty-eyed dream of escape to a better place far from the banks of the Tyne. Water is everywhere, whether looking out across the river and beyond on the deceptively bouncy 'All This Time' or going under for good in 'The Wild Wild Sea' which as a tune, manages to exhibit distinct latter-day sea shanty possibilities. Even the title track, which comes complete with nagging rock guitar motif seems to warn of an eternal watery damnation a full five fathoms below the surface, so much so that it's hard not to put all this down to his "going native" in the Amazon and a greening belief that salvation lies only in the return to a more natural order. Few would argue with that or even the grim Biblical forebodings of 'Jeremiah Blues (Part 1)', one of those jazzy funk items with a bit of disembodied piano-tinkling thrown in that he often favours. In the face of such gushing humanity, the slender Latinate instrumental, 'St Agnes And The Burning Train', comes as a welcome breather.

As one who has built himself virtually from scratch, Sting has proved a master of artifice as well as one of rock's more articulate practitioners. He's not unaware of the ambiguous reaction that his caring, sharing, all-purpose, adult-branded music tends to provoke, nor is he likely to be oblivious to the fact that, in the true spirit of the times, sensitivity sells, especially when it's as carefully packaged as this. Still, let's face it, there are worse things to be accused of.

Review from Rolling Stone magazine by Paul Evans

Something of a pop culture superman, Sting can seem like a daunting - and perhaps overly self conscious - model of higher evolution. A hitmaker erudite enough to quote Prokofiev, a studiously literate lyricist equally fond of venturing into the mists of Jungian psychology and citing such sly ironists as Nabokov, and a millionaire who's fastidiously politically correct, Sting is a rock star of a complexity that never could have been imagined by such raw geniuses as Little Richard. A tireless media crusader for the Brazilian rain forest and a more credible actor than most rockers-as-actors, he's also a proud father and the lurky possessor of looks sharp enough to qualify him as a fashion-mag cover boy. The Renaissance man on hyperdrive, he gulps challenge with every breath he takes.

Highly serious and sonically gorgeous, 'The Soul Cages' is Sting's most ambitious record yet - and maybe his best. Like 'The Dream of the Blue Turtles', from 1985, and '...Nothing Like the Sun', from 1987, it forgoes Police-style catchiness and the safety of conventional song structure for vast swirls of sound that build to either musical or emotional crescendo; the nine pieces are minidramas of intensity and will. What elevates Sting's new music is its freer, deeper and more unified mood. If Sting's deliberate smarts open him up to charges of being an artist who too obviously thinks while he dances, 'The Soul Cages' may trash that perception. It's his most moving performance.

It's also a difficult one. Dense with images of dead fathers and trapped sons, of bitter weather, of moonlight and oceans that threaten oblivion or tempt with release, the songs seldom waver from a deep fatalism that, no matter how romantic its guise, is almost unbearably tense. "Sometimes they tie a thief to the tree/Sometimes I stare/Sometimes it's me" Sting wails on 'Jeremiah Blues (Part 1)', an image that summarises the record's air of struggle, of an aching for deliverance.

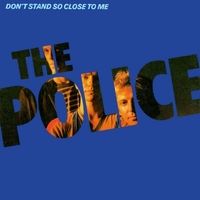

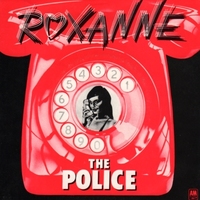

The long-standing sidemen of Sting's solo career, saxophonist Branford Marsalis and keyboardist Kenny Kirkland, undergird a crew of players who seem to relish the test of the intricate, longish material. They flood the sombre 'Why Should I Cry for You' with an elegant yearning, rock steadily on the deceptively jaunty 'All This Time' and turn jazzy and fierce on 'Jeremiah Blues'. Drummer Manu Katche provides complicated, sometimes free, sometimes tight propulsion, and Marsalis remains Sting's ace ally, insinuating graceful, nearly Arabic melodies. Sting's bass playing is supple throughout, and his voice - startling, ever since the Police's 'Roxanne' - has gained subtlety. It's now a truly expressive instrument, whether slurring in a sort of artful Scottish burr or clear-throatedly declaiming. At times recalling the highly textured moodiness of such hip classical movie composers as Angelo Badalamenti ('Twin Peaks') and Ennio Morricone ('The Mission' and any number of spaghetti-western masterpieces), the music has a cinematic breadth.

It helps that the sounds are so enticing. They pull the listener into verbal landscapes that, for all their lush description, are psychic wastelands - cages, snares, dead ends. In Island of Souls, a shipbuilder's son prays to escape the bleakness of his working-class fate: He sees rescue only in flight ("That night, he dreamed of the ship in the world/It would carry his father and he/To a place they could never be found"). In 'All This Time', Christian hope is undercut: "Blessed are the poor, for they shall inherit the earth... And as these words were spoken I swear I hear/The old man laughing/What good is a used-up world, and how could it be/Worth having' The nearly eight minutes of 'When The Angels Fall' form one long, inverse hymn of disillusionment, and 'The Wild Wild Sea' also brandishes a kind of heroic despair: "When the bridge to heaven is broken/And you're lost on the wild wild sea/Lost on the wild wild sea."

Set inside the aural sweep and richness of 'The Soul Cages', Sting's poetic language makes for a sort of sensory theatre - darkly lit, almost Gothic. The effect at times is a bit overwhelming, but it's gripping, too - the tossing and turning of an anxious superman.

Review from Entertainment Weekly magazine by David Browne

On the 'Soul Cages', Sting takes us into his personal heart of darkness. The timing couldn't have been better. Pro-rain forest activist and generally concerned rock star Sting has released his third solo album, The Soul Cages. For maximum environmental protection, the CD is packaged in a "digipack," a fold-over cardboard case designed as an alternative to the wasteful, tree-killing longbox. By an odd quirk of fate, producer Ruth Happel has recently unveiled A Month in the Brazilian Rainforest (Rykodisc; CD, T), four volumes of intensive all-natural sound effects recorded in Brazil. The records not only supplement each other perfectly; they also help answer one of the most vital questions ever considered by man. Which is more irritating-mosquitoes or pompous rock stars

The Soul Cages has little to do with rain forests or any subject as overtly global as Brazilian Rainforest. Like everything Sting has done since the Police established themselves as the most commercially successful of all power-pop bands, the album is intended as a serious artistic statement. Early word of mouth had it that the record would be a return to Sting's rock- oriented roots (especially since he is playing bass, not guitar, for the first time since the Police's 'Synchronicity' in 1983). No such luck, though: The music is more of the same lounge-jazz/pop he's been making since he went solo. There are elements of rock & roll in guitarist Dominic Miller's power chords and solos, but with the rare exception of a mild rave-up on the title song, the guitar is safely tucked away.

Blaring guitars probably wouldn't be appropriate anyway, since the songs are mostly a sullen bunch that explore personal and romantic loss and relationships gone astray, with the recent death of Sting's father casting a shadow over the proceedings. In 'Island of Souls', a shipbuilder's son mourns the death of his dad from a work accident, while Sting's own loss is more directly expressed in 'All This Time' and the mournful 'Why Should I Cry for You' In comparison, the inevitable tract about world destruction, 'Jeremiah Blues (Part 1)', sounds like good news.

Somber themes, even those of an intimate bent, are nothing new for a Sting record. But rarely have songs about feeling awful sounded so stillborn and unmoving. The man was never as much of a sucker for a hook as Elton John was, but throughout 'The Soul Cages', Sting defiantly resists hummability as if a mere catchy pop chorus were too frivolous for such weighty content. Likewise, his latest band-a mix of jazz and rock veterans-seems to be taking its cue from its leader, a man incapable of leaving a simple thought alone. Just when the group settles into a cozy groove on 'Jeremiah Blues (Part 1)' for instance, the mood is broken with a noodling piano break. At other times, the arrangements don't make sense: 'All This Time', which should be one of the record's most touching moments, is upbeat for no discernible reason.

Review from The Baltimore Sun by J D Considine

If making a successful rock and roll album was simply a matter of following a formula, Sting's new album, 'The Soul Cages', which was released yesterday, would be a recipe for disaster.

It isn't that the music is bad. Even though few of the nine songs collected here boast the sort of insinuating immediacy that made his work with the Police so radio-ready, Sting's swirling blend of styles - everything from rock to jazz to R&B to Caribbean pop - is nothing if not listenable.

Listen closely, though, and what Sting sings about is anything but typical hit-parade material. Whether he's forecasting the demise of civilization, as he does in the biting 'Jeremiah Blues (Part 1)', or being haunted by the death of his father, as he is in 'Why Should I Cry for You' and the title tune, Sting's lyrical focus could hardly be called upbeat, much less light-hearted.

It's bad enough that the album's only love song, 'Mad About You', describes romantic passion in terms of desperate insanity. But even the single - the cheerily melodic 'All This Time' - can't stay awayfrom the big issues, wrestling as it does with death and religion.

Can't this guy just write a simple pop song?

Well, sure he can. But what makes 'The Soul Cages' so captivating is that Sting manages to convey most of the pleasures of a simple pop song - the engaging rhythm, the hummable tune - without making the album seem overly simplistic.

If anything, the songs collected here practically beg to be debated and dissected, argued over and analyzed. Part of that stems from the lyrics, which convey all the intelligence of his earlier albums but none of the name-dropping ostentation.

Rather than try to impress us with allusions to Shakespeare and Jung, Sting lets his language speak for itself - and as a result, his lyrics almost sing. 'All This Time' seems a particularly apt example, being filled almost to bursting with vivid imagery and wonderfully poetic language, yet Sting never makes a show of its verbal virtuosity. Instead, he keeps our attention focused on the sound of the song, not in hopes of distracting us from its meaning, but so the music's whimsy is what colors our understanding of the words.

It's not an obvious way to make pop music, but then, 'The Soul Cages' is not an obvious pop album. Certainly, it has enough pop appeal to reward the casual listener, but considering how much more these songs have to offer, it's hard to imagine why anyone would want to give them only half an ear.

Review from The Boston Globe by Steve Morse

Sting, the English teacher turned rock star, has forged his own path since leaving the supergroup the Police in the mid-'80s. He's delved adventurously, if somewhat sleepily, into mellow jazz, didactic protest music and much soft, poetic pop that's a long way from the tougher reggae-rock and funk that the Police often embodied.

But Sting's new album, 'The Soul Cages', which comes out Tuesday, finally balances his experimental tastes with some lift-off rock 'n' roll reminiscent of his Police days - notably the band's No. 1 album of 1983, 'Synchronicity'.

'Soul Cages' takes on a deeper meaning at each listening, and its focus is intensely personal. It is Sting's way of coming to grips with the death two years ago of his father - a milkman in Newcastle, England - and of probing the lives of other working-class heroes who lead equally unsung existences. The album thus has a more immediate, emotional impact than either of his previous solo efforts, 'The Dream of the Blue Turtles' (1985) and 'Nothing Like the Sun' (1987).

Rather than expand upon world problems, which has been a constant preoccupation of the post-Police Sting, he looks inwardly at his relationship with his father and their home life in the rough 'n' tumble city of Newcastle. The lead track, the stately 'Island of Souls', which opens with Northumbrian pipes, is about their living next to a shipyard, where a ship would grow before their eyes and "her great hull would blot out the light of the sun." Sting imagines his father as a shipyard worker, and dreams that they would escape on one of the ships "to a place they could never be found, to a place far away from this town... they would sail to the island of souls."

This escape motif - and this same last verse - shows up again in the title track, a Police-like rocker that talks about "The souls of the broken factories... the souls of the broken town; these are the soul cages." It's a wrenching, Joe Hill-like anthem for the '90s and comes with visceral soprano sax fills from longtime accompanist Branford Marsalis, and gospel-nodding organ lines from David Sancious, an early member of Bruce Springsteen's E Street Band.

Sting's father reappears in the ballad 'The Wild Wild Sea', a bracing goodbye suffused with more elegiac pipe sounds. Sings Sting in his most beseeching tone, and in couplets befitting his English-teacher past: "For the ship had turned into the wind/Against the storm to brace/ And underneath the sailor's hat/I saw my father's face/If a prayer today is spoken/Please offer it for me/ When the bridge to heaven is broken/And you're lost on the wild wild sea."

The album builds powerfully. 'Jeremiah's Blues (Part 1)' is another rocker reminiscent of the Police, and deals with trying to turn away from pain. 'Why Should I Cry for You' is a multitracked, Peter Gabriel influenced ballad that furthers the catharsis. And the concluding ballad, 'When the Angels Fall', with a panoramic, soundtrack-like synth fadeout, is Sting's last word on his dad: "Take your father's cross/Gently from the wall/A shadow still remaining."

This is no album for the squeamish, even though some of the musical colors are soothing (as in the classical-guitar instrumental 'St. Agnes and the Burning Train'). Overall, Sting has fashioned a well-balanced, highly insightful record that functions as a musical diary of the heart.

Review from The Arizona Republic by Jim Rosenberg

Sting's third solo album, 'The Soul Cages,' maintains much of the vitality and energy of his other solo work, yet it has a sound that is uniquely its own.

The sound has something to do with the album's theme - the death of Sting's father.

'The Soul Cages' begins with a somber, haunting melody that deals with ''Billy'' and his father, the shipbuilder. Sting employs Northumbrian pipes, exclusive to northern England, to give the track a cold, pallid feeling of loneliness and alienation. It's not the uplifting, buoyant sound Sting has been associated with in the past. He has a message to convey, a story to tell, and he does just that.

Then comes the first single, 'All This Time'. The track seems like a departure for Sting because most of his solo work is typified by jazzy wind instrument solos and clear-cut, easily-understood lyrics.

'All This Time' seems like it could have been done by the Police considering it's tight percussion and well-woven harmonies, proving that an artist doesn't have to choose between good lyrics and good instrumentation. 'All This Time' combines the best of both worlds.

'Jeremiah Blues (Part 1)' also is notable for its tight percussion and precisely-crafted melodies. Like most of the other tracks on 'The Soul Cages', 'Jeremiah Blues' gives the listener a feeling of awe, a sense of musical travel to another place and time that can only be experienced by listening to the album.

Sting's style has evolved from one of edgy and rough rock to a more smooth and defined ''jazz'' sound. He's probably the only artist that can be heard on album rock, Top 40, alternative and new age radio.

Sting's newer style is an evolution. It's different from the Police. When compared, it should be kept in mind that the style of Sting's earlier work is just as valid and just as powerful and unique as his later work. The only difference is that the style has changed.

Whether for better or worse is left to personal tastes. I like both.

Review from The Dallas Morning News by Tom Maurstad

Entering the fourth year since his last release - '...Nothing Like the Sun' - Sting was in danger of falling prey to that final stage in the celebrity process: People lose track of what made you famous in the first place. Songwriters write songs, after all, and maybe Sting the Spokesman had so much to say because Sting the Songwriter had nothing left to say. And then along comes 'The Soul Cages'.

This is Sting's fourth solo album, and as is quickly made clear, he has been doing - of all things - a lot of thinking since last he spoke through song. Already the cycle of expository interviews has begun, initiated in Rolling Stone. Among the salient items to keep in mind while responding to this album are that Sting's parents died, that his denial of grief threw him into a protracted bout of writer's block and that he had reached that ominous middle age (38) where he found himself wanting to look back and "assess' his life - oh dear.

So Sting has done what one would expect Sting to do. He has written a satchelful of moodily introspective, metaphor-laden lyrics, applied them to pop melodies laced with plenty of Third World rhythms and the odd jazz/classical figure. And to present them, Sting has gathered an ensemble of superlative session players, including his 'Blue Turtles' associates Branford Marsalis and Kenny Kirkland. His arrangements create a lush, vaguely exotic sound with their complex blend of strings and horns and keyboards and always the chatter of percussion.

Meanwhile, his lyrics wend their way through a collection of sometimes somber, sometimes animated, but always serious reflections. The themes of life and death, renewal, denial and abandonment are so overtly drawn that the experience of listening to these songs is akin to reading English Lit exercises in which you must find the metaphors, allegories and what have you.

Ships sailing out to sea, rivers flowing into seas, kingdoms turned to dust, a son haunted by a dead father - Sting is a heavy guy, and this album is a work of obvious intelligence. But that blade cuts both ways; Sting's intelligence is both clear and predictable. This results in some striking images and couplets, but self-consciousness hangs heavily about, and one always is aware that this means something; intention is always explict, the lessons never inadvertent.

As a result, this album never stretches beyond technical virtuousity and intellectual panache. For all the soul-searching and summing up, the music is suffused with a sense of detachment, of posture and emptiness. Sting has given this music style and refinement aplenty, but his is a spiritless solitude, and his music is, to use one of Sting's favorite adjectives, bloodless.

Village Voice music critic Robert Christgau once observed that in almost every instance, rock didn't work if it wasn't fun. 'The Soul Cages' is simply no fun. Not just in the strictly entertaining sense of fun, but in the larger sense of involving passion, abandon, spontaneity and release. The only song to generate any life beyond its meticulously orchestrated form is the first single 'All This Time', which is blessed with an irresistible hook and some refreshingly homespun mandolin.

Sting is able to work up some intensity when he returns to his favorite theme, the relentless pursuit of one's obsession. 'Mad About You' is the latest entry in his 'Every Breath You Take' canon, going so far as to rework that song into the line "But every step I thought of you/Every footstep only you.'

But too often this is an album about thinking rather than simply feeling. There is lots to admire. But when Sting draws his circle to a close, reintroducing the theme from the opener, 'Island of Souls', as the chorus of 'The Soul Cages' near the album's end and alters the pivotal line "He dreamed of the ship in the world' to become "He dreamed of the ship on the sea,' you just know that it's supposed to mean something, that it's significant.

Review from The Baltimore Sun by Nestor Aparicio

With the release of his latest album, 'The Soul Cages', Sting has distinguished himself as one of the world's biggest touring rock star who hasn't written a rock song in eight years.

Where its two predecessors, 'The Dream of the Blue Turtles' and '...Nothing Like the Sun', were basically jazz fusion works laden with pop influences, 'Cages' portrays a distant, almost new-age sound.

Only two songs on this departure album bare any pop sounds at all; the bouncy 'All This Time', wisely chosen as the first single, and the title track, which is led by the big drum sound of Manu Katche and the light guitar riffs of Dominic Miller.

The entire album seems to center on the grief endured by Sting after the death of his father three years ago. Sting has revealed in several interviews that he incurred a terrible "writer's block'' during the process of putting the album together and that he attributes it to the fact that he never completely dealt with his father's death.

Well, here, in 49 minutes of lush, beautiful sounds, Sting truly wears his heart on his sleeve.

It turns out that musical and instrumental pieces came very early and easily in the recording process, but the words were extremely difficult to muster.

Sting has said he tried to recall the first images of his childhood to incite words, and once he thought about the shipyards of his hometown of Newcastle the words of the water and the images of the "rivers flowing endlessly to the sea'' all came in less than one month.

Seemingly impossible to pigeonhole, Sting, now 39, enters yet another era in his stately catalog of music and achievements.

Except for the raspy vocals, 'The Soul Cages' certainly bears no resemblance to any of the work of The Police. The brassy arrangements of his first two solo works are nowhere to be found, despite the return of Katche (drums), Kenny Kirkland (keyboards) and Branford Marsalis (saxophone) to the project.

It wouldn't be a major surprise to see the album sell far below any of his previous works - it obviously wasn't written with a pop audience in mind. But, remember, the critics said the same thing about 'The Dream of the Blue Turtles' in 1985.

Review from The Los Angeles Times by Chris Willman

Not since Roger Waters spent one-and-a-half concept albums mourning his father has a pop star dealt so blatantly with familial loss - though Sting's muted grief is expressed, as you might expect, less howlingly and more elegiacally.

Peaceful as he sounds in these relaxed grooves, lyrically Sting seems far from reconciled to his father's death. Taking his cues from Job and Solomon, the singer takes on God more than once - berating the priests who've come to bless his dying father in 'All This Time' (the first single!), angrily demanding that the angels be cast away from his sight at the climax. In their stead, he offers river and sea imagery - lots of ships and watery continuums - as his alternate spiritualism. On an anti-religious bent, he's as provocative as poor Madonna wishes she could be.

So it's not exactly the feel-good hit of the winter. Only one song, 'Jeremiah Blues', on this lovely downer of an album has the studied jazz funkiness that made prior Sting efforts percolate. 'The Soul Cages' is a quieter and less immediately satisfying outing than '...Nothing Like the Sun', which had Sting painting on a much broader canvas.

When it comes to the dying of the light, he doesn't rage very hard, and delivers much of the tough stuff in an even, dispassionate clip that will fuel the standard line of his detractors - that he's "cold." But whether you find his themes brave, touching, pretentious or all of the above, taking on dad, deity and death as a melancholy trinity is ample evidence of his encouraging disregard for the marketplace cages.

Review from The San Jose Mercury News by Harry Sumrall

What is there left for Sting to do With the Police far behind him, a creative and commercially successful solo career established with such records as 'The Dream of the Blue Turtles' and '...Nothing Like The Sun', and with his dabblings in movies and his 1990 Broadway debut in "The Threepenny Opera," it would seem that there is little left for Sting to attempt or accomplish.

Perhaps that is why 'The Soul Cages', his first studio record in four years - released today - seems somewhat tentative. There is about it a sense that Sting is marking time, waiting for a new creative direction, just playing on until it comes. If only the rest of rock could play on in such a manner.

Its tentativeness notwithstanding, 'The Soul Cages' is a ravishing record. With little to prove, Sting has simply allowed himself to sing and play with an exuberance and a dexterity that are astonishingly pleasurable. It begins with moaning Northumbrian pipes that give way to the brooding 'Island of Souls', a song whose instrumental complexity is tempered by a basic story imbued with a quasi-autobiographical intensity. Sting is back among the shipbuilding docks of his youth, decrying the lot of the workers and their lives. Although other personal references make their way into the record (it is dedicated to his late father), it is the theme of frustration and desperation - and the questions that come with both - that prevail. Again, it seems, Sting is taking stock.

But 'Island' gives way to 'All This Time', one of those clicking pop ditties that Sting dispensed with the Police. Only now, the lyrics have become somber and reflective. Old sounds, new thoughts and questions and doubts. The rest of the record goes off on various tangents. There is the Brazilian feel of the instrumental 'Saint Agnes and the Burning Train', with none of the pedantic fervor of Paul Simon's 'The Rhythm of the Saints', only the beauty. And there is the energy of the title cut - oddly, the only rocker of the set. And there is the grandeur of 'The Wild, Wild Sea', in which Sting blurs the barriers between rock and jazz and pop with an almost effortless ease, much as he did with 'Sun'.

A few of the songs are less convincing. 'Jeremiah Blues (Part 1)' is a trifle too facile and flaccid for its own good. And 'Why Should I Cry For You' and 'When The Angels Fall' are ambiguous, as if Sting had nothing to say, but two empty tracks left on the record.

But on the good songs and bad, Sting is still Sting. His voice is incomparable, with its stinging highs and ebullient sleekness and its unerring sense of when to err, to crack and break only to resume its steady, smooth course. He is also playing bass again, after yielding to other and technically better bassists on 'Turtles' and 'Sun'. But playing his bass seems to endow his songwriting and vocals with an added urgency, makes him more involved in the music-making process.

All of which is to say that even in his ambivalent state, Sting is still a class act. 'The Soul Cages' doesn't have the innovative excitement of 'Turtles' or the creative elan of 'Sun'. But it does have Sting in all his performing and songwriting finery. And that is good enough for now.

Review from The Sunday Herald Sun (Australia) by P Speelman

Sting has come a long way since escaping the clutches of the Police. Since going solo with 1985's 'The Dream Of The Blue Turtles', he has moved away from relying on repetition and using that vibrato-free voice of his to startle. Just how far he has come is shown on 'The Soul Cages', his first album since 1988's 'Nothing Like The Sun'. (He claims the three-year hiatus was caused by writer's block, not having written "as much as a rhyming couplet" by early last year when he was expected to start work on an album.) Reunited with saxophonist Branford Marsalis and keyboardist Kenny Kirkland, his two main collaborators from the previous solo albums, and underpinned by Manu Katche sympathetic drumwork and his own bass, Sting's voice is now more subtle, more like a musical instrument.

But what sets him apart from the boys here is his writing, and his arrangements. Imagery is to the fore (And all this time the river flowed, endlessly like a silent tear, from 'All This Time') and the arrangements - from the dramatic ('The Wild Wild Sea') to the majestic ('Why Should I Cry For You') to the fiercely jazzy ('Jeremiah Blues') - fill in the musical pictures being painted.

With swirling but intelligently used keyboards and strings - and sax, oboe, mandolin and Northumbrian pipes supplying the counterpoints - Sting draws into his aural web the listeners who might otherwise resist the fatalism that confronts them: lost souls, bleakness, dead fathers, trapped sons. 'All This Time', which at least sounds jaunty, has been released as a single but I can't see too many other candidates for a follow-up; which is not to say that there aren't fine moments among the nine tracks. I particularly like the mid-European gipsy sounds of 'Mad About You'; the quirky, uptempo jazz beat of 'Jeremiah Blues'; Sting's singing over Katche's threatening drums and the poetic images of 'The Wild Wild Sea'.

This may not be the accessible Sting of the Police days but it's every bit as arresting - and much more challenging.

Review from Playboy magazine by Vic Garbarini

Welcome to rock's mid-life crisis. Artists such as Paul Simon, Bruce Springsteen and Sting are being nudged by their muses to explore how rock can remain vital and relevant to their increasingly adult audiences. Sting's latest, 'The Soul Cages', falls stylistically and musically midway between Simon's exotic dreamscapes and Springsteen's earthy epiphanies. 'Soul Cages' is a return to the singer's roots - a slow-motion, volcanic expulsion of many of the toxins and torments that he instinctively traces back through his childhood among the factories and shipyards of England's northeast coast to his relationship with his recently deceased parents, particularly his father. The sea imagery is highlighted in the spry single 'All This Time', which recalls mid-period Police, courtesy of guitarist Dominic Miller's deft fills and voicings. Sting's use of archaic Coleridge/Melville imagery knits the song cycle together thematically. It can be cumbersome and awkward, but when he jettisons the metaphors and speaks directly from the heart, the results are deeply compelling. 'Why Should I Cry for You' is 'Every Breath You Take' turned inside out, a raw and moving reconciliation with the ghost of his father. This is rock for adults who want to heal those inner wounds, not just howl about them.