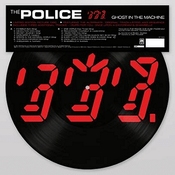

Ghost In The Machine

- Spirits In The Material World lyrics

- Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic lyrics

- Invisible Sun lyrics

- Hungry For You (j'aurai toujours faim de toi) lyrics

- Demolition Man lyrics

- Too Much Information lyrics

- Rehumanize Yourself lyrics

- One World (Not Three) lyrics

- Omegaman lyrics

- Secret Journey lyrics

- Darkness lyrics

Soundbites

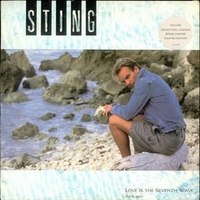

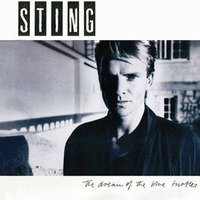

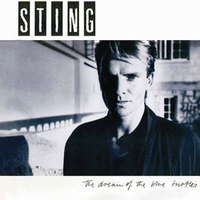

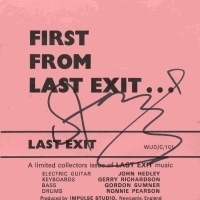

'Ghost In The Machine’ was The Police’s fourth album which was first released in 1981Recorded at AIR Studios, Montserrat and Le Studio, Quebec, ‘Ghost In The Machine’ was number one on the UK album chart and a multi-platinum best seller all over the world in which the bands’ jazz influences became more pronounced but still retained the sophisticated pop appeal for which the band becamee known. The original release featured three hit singles -‘Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic’, ‘Invisible Sun’ and ‘Spirits in the Material World’. Other highlights also include the rollicking ‘Demolition Man’ (later covered by Grace Jones), the frantic ‘Rehumanize Yourself’, and the ballads ‘Secret Journey’ and ‘Darkness.

"Apart from 'Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic', all of the songs on this album were written in the west of Ireland in 1981. I borrowed the title from Arthur Koestler's 1967 book about the human mind and our seeming appetite for self destruction. The book talks about how the modern brain of Homo sapiens is grafted onto older and more-primitive prototypes and how in certain situations these reptilian modes of thinking can rise up and overcome our higher modes of logic and reason. I tried, as far as it was possible in a collection of pop songs, to deal with some of these issues. Violence in Northern Ireland in 'Invisible Sun', skinheads and Nazis in 'Rehumanise Yourself', destructive pathology in 'Demolition Man', lust in 'Hungry For You'. The album was densely layered with multitracked vocals, synthesised keyboards, and horn riffs played by yours truly. I wanted to create the impression of something struggling to the surface, something hidden in the recesses of the mind, something from our dark subconscious wanting to be seen. The album cover showed our three faces transposed into digital images, red LED lights on a black background. We were the ghosts in the machine, and while some of the songs are a plea for sanity, others are an expression of that malevolent darkness that haunts us all."

Sting, 'Lyrics', 10/07

"In the record I have ideas put very simply which are parallel to the ideas put very coherently over hundreds of pages. 'Spirits In The Material World' says there's no political solution to what's happening to us, it involves transcending our condition. 'Demolition Man' is the beast, he can't help himself, he has to destroy. That's part of me, I'm actually very destructive, I can also be creative, but that is half of me. 'Re-humanise Yourself' is a parallel idea to Koestler's that we're becoming dehumanised through work systems, through political systems, through convention. 'Hungry For You is in French', because it's filthy, and French is the language of love."

Sting, NME, 9/81

"The reason we have to attack Behaviourism is because it's been used by totalitarian regimes as an easy way of making people conform. A robot fits into big ideas much better. Whereas a thinking human being, a complex spiritual being, which is what we are, is out of place. You only have to look at the kids on the streets, they're becoming de-humanised. A gang of skinheads can be machines, hateful. And it's not their fault, they're being used. According to Koestler there are two brains. Well, there are three, but for our purposes there are two. There's the old brain that the lizards have which involves fear, hunger, aggression, sex, the beast in us. The other brain is quite a recent addition and involves abstractions, things that transcend the body. Unfortunately the two brains are entirely separate and there's no communication between them. Therefore there's a kind of schizophrenia. One side is looking at the stars and wanting to transcend the human condition, and the other side is grovelling round looking for the next person to rape or beat up. I think he's right, that is what's wrong with us. He does offer a solution which is a bit extreme, but I think he does have a point. I won't tell you what it is or I'll spoil the book."

Sting, NME, 9/81

"'Ghost In The Machine' is a very punchy album. It's getting harder, year by year, to make the grade. As the years go by the spotlight gets bigger and makes you sweat more. I would say that we've broadened stylistically and it's true to say that Sting's voice has a greater range. In the old days I think he used to sound something like Yes's Jon Anderson but now he's got a lot more bottom to his voice. All of us are worried about the quality of our records and performing. All of us are constantly critical about the things we do. You see it's not the similarities that makes this band - it's the differences. By that I mean that if we all got on well all the time and agreed about everything there would be no creative tension. We'd amble off into a recording studio from time to time and produce garbage. I'm sure that for any band to achieve longevity they must have creative tension.

Andy Summers, A Visual Documentary, '81

"Before we come together for an album, each of us goes into a studio of our own. I wrote ten songs for this album, and with a drum box, piano, bass and guitar put down the arrangements as I saw them, as best I could. If they were satisfactory to the group, that's what we played. If they could be bettered... I'm proud to say that in a lot of cases, the arrangements I came up with at the demo stage arrived on record. 'Don't Stand So Close to Me' is virtually the same as the demo, and 'De Do Do Do', on the new album, 'Invisible Sun' and 'Spirits in the Material World'."

Sting, Musician, 12/81

"Whoever wrote the song will show the others the chords. In my case, I don’t know the names of ‘em so I just play ‘em. Andy looks at my fingers and says, ‘You moron, that can’t be done,’ or why have you done that’ and everybody figures out whatever they can. In Montserrat, Andy was in the studio, Sting in the mixing room playing through the board and I was in the dining room in the next building. We all have our cans [headphones] on; while they get the chords I fiddle with the rhythms. Then we run through it once. Usually, somebody plays too many times around the chorus or something that’s not right, and we do it once more. If we haven’t got it then, it starts to get lost. Usually we have, though; 'One World (Not Three)' was right the very first time, for instance."

Stewart Copeland, Trouser Press, 4/82

"The horns happened by accident. I brought a saxophone in and during the vocal tracks I first started to play sax lines and I thought they were fun so it ended up that I took a tenor and an alto and ended up overdubbing them four times like a brass section. It shouldn't have been done because I'd only been playing saxophone six months, but it did. And that additional colour - affected the whole atmosphere of the album, the whole thing, it just changed it into what it became."

Sting, Guitar World, 7/82

"'Ghost' was, for us, a please-yourself album. In it we pleased ourselves. Our last records were experiments in commercialism. I'd been obsessed with the idea of coming up with a commercial record. 'Ghost' doesn't have that concern. It's just... us. I wouldn't say we were totally non-thinking before it came along. It's just that in the past a function of our music has been to be a catalyst for certain feelings. After our first three albums, we wanted to go as far away from the sound we'd already created. I was determined to play some saxophone. Generally we wanted to go off the beaten path, to take a fresh new approach and see what happened. I think the material that came out on the next albums was stronger. It was something we all believed in. By our third album we realised it came too close in sound to the albums before it. The balance had been tipped too much toward commercialism. We'd become almost obsessed by it largely because the only group who was selling any records in Europe for a year or so was The Police."

Sting, The Police Chronicles, '83

"Things were getting very horrible. Very dark. Miserable. Our marriages were breaking up, our marriage was breaking up and yet we had to make another record. Nightmare. Then it hit us that this is how we're going to have to make our living for the rest of our careers. I started looking for a way out. It was too much of a shock because I said from the beginning the Police will last three albums and well, we did really."

Sting, Q, 11/93

"I have to say I was getting disappointed with the musical direction around the time of 'Ghost In The Machine'. With the horns and synth coming in, the fantastic raw-trio feel - all the really creative and dynamic stuff - was being lost. We were ending up backing a singer doing his pop songs. But there were still great moments when Sting was able to loosen up enough, where we could really go for it in concert."

Andy Summers, Guitar Player, 1/94

"The title is taken from a book by Arthur Koestler about comparative psychology in which he states that man is becoming more machine-like, and what I'm saying is that we shouldn't be like machines. We're much more complex, more creative, more destructive."

Sting, A Visual Documentary, '81

"If one person reads "The Ghost In The Machine" because our album has the same title, then I think it's a good excuse to have called it that. They're ideas that gestate, and now I'm at the stage where technically I can write songs that I would have found really difficult two years ago. I now feel capable of writing objective songs and I think that's an improvement. That's not to say that I can't go back and write very personal songs, but my concerns at this moment aren't whether I have a number one record this week, or whether we sell ten or seven million, or whether we're the biggest group in the world. My concern really is whether there's going to be a world left for us to be successful in. Michael Foot was right, everything else is trivial and childish. The real issue is whether we're going to survive as a race."

Sting, NME, 9/81

"It would be pretty pompous if I turned round and said this album is going to change the way people think. However, you have to chip away, you have to give something. I have a medium at my disposal a forum, if you like, in which to discuss ideas. I'd be untrue to myself if I didn't try to say what I believe in, in that medium. I don't know how far you can go, to a certain extent it's all rhetoric. There's a line in one of the songs that says "the words of politicians are merely the rhetoric of failure" and I don't claim that much more for my own rhetoric, except that I have no other choice but to say what I believe in now. I'm free of shackles; so I think I can do it. It won't change society, of course it won't. But what I would like is for people to read the book, because I think it has some great ideas, very simply and coherently put, which the songs give a glimmer of."

Sting, NME, 9/81

"This is the fourth album. By the time you get to this point, most people usually start softening up. For us, it was very important to bring out a very strong, punchy album."

Andy Summers, Musician, 12/81

"I used to play saxophone as a teenager although not very seriously. The fingering has always stayed with me, and I can read music, so getting back into it was fairly simple. I bought a Yamaha alto and tenor in January and spend about two hours a day, the fruits of which you can hear on the album. It's section work, really. I'm no Charlie Parker, but it's very satisfying getting a simple riff together, then dubbing it and putting harmony on it. The skills involved are fairly similar to the ones you use in singing; you know, breathing, pitch, a sense of harmony."

Sting, Musician, 12/81

"It's a fair comment to say that there's a little more of a rhythm and blues feel on the new album. We never said, 'Okay, let's make this a more soul-oriented album,' but on some of the tracks there's definitely that sort of James Brown edge to it."

Andy Summers, The Washington Post, 1/82

"I'd written four or five of the songs on the new album on keyboards so in a sense that was an extra colour as well. Having written them on keyboards, I recorded them with keyboards. I'm talking about 'Invisible Sun', among others. So in a sense we've broken away from the thing which first made us. Well, 'power trio' was a misnomer in the sense that it made us sound like Cream or Jimi Hendrix. I think we're much lighter than that, so I don't usually take that blanket title with much seriousness. We're just getting away from the sparse sound of three instruments and a voice - we're more interested now in just selling our songs in a bigger way. Maybe we've gone through the cycle now. Perhaps we'll go back to a sparser sound."

Sting, Guitar World, 7/82

"I didn't think the book had any particular relevance to my understanding of the album's lyrics. At the same time we had a million titles written up on the studio wall including 'Blanco De Bunker,' and a lot of similar ones we didn't use."

Stewart Copeland, Creem, 4/82

"I'm plagued by mystics. Ever since 'Spirits In The Material World'...it's become the theme song of all kinds of weird religious groups. They keep writing to me, they keep turning up with bald heads and ponytails and pink dresses. It's like I've become this kind of focus point for gurus. I mean it's something that I'm interested in but it's very odd that all these people are suddenly turning up."

Sting, USA Press Conference, '82

"I enjoyed making 'Ghost In The Machine' and playing with the tools of the studio, just building things up and sticking more vocals on. Great fun. But listening to it, I thought. "Hey, my voice on its own sounds as good as fifteen overdubs, so I'll try it on its own." And I've done the saxophone section bit now, I'm bored with it; and Andy was into just plunking down one guitar part. I'm glad we did 'Ghost'. I don't regret it. But it was time to change the regime again. A lot of the criticism levelled at us and that album was that we're incredibly formula-ised and efficient. Almost Nazi-like..."

Sting, Musician, 6/83

"I think it's very strong. It has a supple quality I really like, and a very positive vibe I think was lacking on the last album. It's a true reflection of the psychological state the band was in."

Andy Summers, Creem, 4/82

Backgrounder

Review from The Guardian by Robin Denselow

After a week in which a packed Festival Hall audience was actually singing along to the quaint warblings of the ever-twee and boyish Donovan, and when the Grateful Dead were back yet again at the Rainbow, it really did seem that the psychedelic Sixties were again upon us. But if there's to be a psychedelic revival, as predicted by those who seem to have run out of anything else to revive, then I suspect that it won't come in the obvious styles currently being touted by the new bands dressing up in paisley, velvet and Byrds haircuts. The real innovations of the best Sixties' psychedelia were not in the trappings but in the music and attitudes - and here there's some evidence that some of the best, and most unlikely, new bands are echoing such styles and sentiment, though in a more sophisticated and hard nosed way.

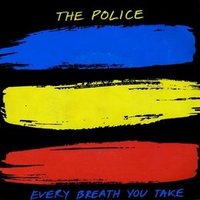

Take, for instance, the fascinating new album by The Police: 'Ghost In The Machine'. Those listening out for obvious hit singles along the lines of 'Message In A Bottle' might be disappointed, for this most massively popular of our newer bands has shied away from the white reggae/pop format to produce an album that at first listening may seem less commercial than before, but which in fact is a major, subtle departure, particularly where the lyrics are concerned. The title comes from Arthur Koestler's philosophical work, which seems to be Sting's current bed-time reading. He's always written intelligent lyrics to his pop hits, but suddenly he's developed a far bolder, broader vision. It's tempting to make a comparison with the mid-period Beatles emerging from a pop formula to write songs attempting to analyse the world around them - except The Police have found no gurus and no simple solutions.

Instead, and this is the link with the Sixties, there's an almost mystical, non-specific religious interest cautiously creeping in. It's there in the opening track, 'Spirits In The Material World', with its assertion "There is no political solution," and it's there on the third track, the current hit single 'Invisible Sun'. If 'Ghost Town' was the single of the summer, then 'Invisible Sun' is the single of the autumn, mixing as it does bleak reportage with a sudden, unexplained ray of hope. The song was written about Belfast (which makes it braver still), and such lines as "I don't want to spend the rest of my life looking at the barrel of an Armalite" are offset with the thought: "There must be an invisible sun... that gives us hope." It's an album of thoughts and questions rather than simple answers, and these range from the semi-religious to the semi-political. So elsewhere, 'Too Much Information', 'Re-humanise Yourself', and 'One World (Not Three)' tackle the subjects that those titles suggest.

The final 'Secret Journey'. gives another hint of inner peace and outer turmoil. The music to all this is as sophisticated and as direct as the lyrics. The reggae feel is still there, but so too is a stomping Rhythm and Blues style. Many of the songs are pared right down to very simple throbbing bass riffs over which guitarist Andy Summers adds a complex embroidery. Sting's newly-developed skill as saxophonist fills out the sound (listen to the treatment of the very simple, pounding 'Demolition Man') so any new mysticism is offset with an Eighties' hard edge.

Review from Rolling Stone by Debra Rae Cohen

Esperanto, like the League of Nations, was one of those good ideas that just didn't work. Intended as an international language not native to anyone but foreign to no one - an answer to divisiveness dating back to the Tower Of Babel - it failed because its design gave a sop to every culture while capturing the passion of none. The same is often true of pop music that attempts to meld the resources of various countries. Native idioms, when taken out of context, can lose their indigenous spark or be reproduced so painstakingly that they become ridiculous in a pop context. The bridge that many groups try to build to the Third World sometimes uses condescension for its supports. By their second and best LP, 'Reggatta de Blanc', however, the Police had managed to devise a musical Esperanto that succeeded. Bathed in the watercolour wash of guitarist Andy Summers' chording, the band's rhythms and inflections merged into a homogenized yet utterly distinctive sound that didn't revere its components as much as recontextualize them, creating new passion in fresh places.

The group's approach was relentlessly, calculatedly middlebrow: never identify, never over explain, flatter your audience into thinking they appreciate cross rhythms when what's really hooking them is some of the snappiest songwriting since Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller. Buttressed by the band's earnestly liberal message, this approach clicked. 'Zenyatta Mondatta', the third Police album, made the Tope Ten. In a strange way, its sound was so familiar as to be formulaic: Sting's high, lilting singing, Summers' shivery harmonics and, most of all, the music's spare, sculptural quality - the way each number had a core of space in which rhythms changed and grew and echoed. 'Ghost In The Machine' downplays most of these elements - or, rather, augments them. Chords don't reverberate in a shaft of silence but find response in overdubs. Sting's thin vocals have harmonising partners. The multitrack singing eliminates the attractive tinge of aloneness that's always been integral to the subtext of Police compositions, while the extra instrumentation - keyboards, guitar parts, Sting's overdubbed one-man horn section - fills up the open spaces in their music.

'Ghost In The Machine' feels unsettlingly crowded. Which is as it should be, since that's what the album is about: overload, media explosion, the global village, the behavioural sink. The Police's platform, a spin-off from Marshall McLuhan, Alvin Toffler, et al., is hardly news (sure, 'Ghost In The Machine' is a smart, track-it-down title but author Arthur Koestler hasn't been in vogue for quite a while), yet it's strongly stated, consistent and compelling. The thrashing, denatured funk of 'Too Much Information', the whirlpool riff that punctuates 'Omegaman' and the oppressive, hymn like aspects of 'Invisible Sun' all bespeak claustrophobia and frustration, and the lyrics bear them out. The Police skilfully manipulate musical details to underscore their points. Sting brays "information" as if to demonstrate how words, when repeated enough, can disassemble into meaninglessness.

In 'Rehumanize Yourself', the singsong circus-calliope mood of the music works as a taunt to the raw seriousness of the lyrics: "Billy joined the National Front / He always has a little runt / Got his hand in the air with other cunts..." They're still not the Clash - neither the National Front nor the situation in Belfast (broodingly addressed in 'Invisible Sun') is an especially risky target - but the Police display more commitment, more real anger, on 'Ghost In The Machine' than ever before. It's as is their roles as self-anointed pop ambassadors have shown them the difficulty of healing gestures. For example, the heart-rending joyousness with which 'Every Little Things She Does Is Magic' bursts from the grooves proves its discontinuity with all of the other songs. It's a moment of liberation, of tossed-off shackles, whereas the rest of the record (even, to some extent, the obsessive 'Hungry For You') emphasises constraints - if not those imposed by society, then those accepted as responsibility, like the toll that talent exacts in Stewart Copeland's 'Darkness' or the promise to continue to seek knowledge in 'Secret Journey'.

Even 'One World (Not Three)', a sort of reggae march that's the closest the LP comes to an anthem, is a kind of trial: by attacking the concept of such categorisations as the Third World, the tune turns inwards to interrogate the Police themselves, implicitly questioning the attitudes involved in their rock-around-the-world crusades. Not so incidentally, the number is also a virtuosic instrumental display, particularly by Copeland, whose drumming captures both reggae nuances and rock & roll dynamics. On 'Ghost In The Machine', not even genius exempts you from tough questions. The Police's smarts have always been greatest when they didn't show - in making unorthodox career decisions or disguising the subtlety of their songwriting as simplicity. Now that the group has been rewarded with success, it's time to change, to challenge old assumptions. Having seen the world, these guys are starting to look more closely at themselves.

Review from People

The premier purveyors of reggae-rock offer more of a pop base to their music after three splendid, formative albums. And yet Sting's thundering, rampaging bass, a reggae remnant, still dominates this English trio's brilliantly inventive sound. Rather than resort to flashy instrumental breaks, they create rich, electric textures with Andy Summer's hard-metal guitar chords, Sting and guest artist Jean Roussel's synthesisers and Stewart Copeland's whipcrack drummings. The album lyrics, all but indecipherable, have vaguely apocalyptic titles like 'Demolition Man', 'Rehumanize Yourself' and 'Invisible Sun'. The hit single 'Every Little Things She Does Is Magic' starts off slow and then doubles in speed much like 'Message In A Bottle' from 1979's 'Reggatta de Blanc'. Sting's vocals now are moving away from his mock-Rastaman inflections towards a broader rock delivery. The other tunes exploit to just the right degree space-music synthesisers and hard-edged driving funk-rock. Everything this group does is magic.

Review from Musician magazine by Jon Pareles

'Ghost In The Machine' confirms something I'd suspected all along; that the Police never set out to be white-reggae popsters. It was kind just that reggae and pop (the AM kind that goes hook-hook-hook-hook...) offered the easiest, most format-digestible camouflage for the Police's real obsessions: repetition and syncopation, preferably both at once. On last year's 'Zenyatta Mondatta', the band started to break away from its self imposed sound, and 'Ghost In The Machine' (which even dispenses with the pig-European title schtick) makes its ambitions overt.

The songs are all recognisable vocal lines - with Sting's characteristic vocal lines and four-bar units; Stewart Copeland's swinging, accents-on-two-and-four drumming, and Andy Summers' ultra-float textural, non-linear guitars - yet only 'One World (Not Three)' openly recalls reggae. For the rest, the beat varies from JBs to light metal, but the basic strategy doesn't. If you listen to the album through transistor-radio-sized speakers, you'll hear the main, midrange riff of each song again and again; on a better system, you'll notice the band's experiments with new arrangements (like horns, keyboards, tape effects) and a bunch of inventively repetitive inner parts. This time, the Police are seriously minimal; Invisible Sun even tips its hat to Philip Glass with a count-off that's just like the ones in 'Einstein on the Beach'. The Police's ambitions extend to their lyrics, with more mixed results. Now that they've seen starvation and poverty first hand (on their India tour), they seem impatient with boy-girl stuff.

Unfortunately, their political statements come across just as poppy - as superficial - as the rest of their repertoire; i.e. when they can come up with a catchy refrain like "Too much information / driving me insane," it works fine, but when in 'Rehumanise Yourself' they sink to rhyming "national front" with "c****" - used as an insult! - I wonder how deep their humanism goes. And when they wax lyrical on 'Invisible Sun' and 'Darkness', well they're right up there as revelation-bearers with George Harrison. But 'Ghost In The Machine' shouldn't have to stand on its text any more than Pharoah Sanders' 'The Creator Has A Master Plan'. If the album is about anything, its subject is the way Andy Summers is drawing together Hendrix (in 'Demolition Man'), Zawinul (he's found the guitar equivalent of 'Milky Way' for 'Darkness') and Steve Cropper; or the way Copeland knocks around his cymbals, or the counterpoint Sting insists on writing - or the way the whole band propels songs without harmonic motion. The Police have proven themselves, not only as musicians, but as popular musicians, doing that rare, graceful balancing act between vox populi (x hooks per minute and catchy choruses) and their own agenda - Einstein on the top 40. If they can hang onto their sense of humour, so much the better.

Review from Circus magazine by John Swenson

The fourth Police album is a conscious attempt on the band's part to break violently from the formula that made them one of the most promising bands of the '80s. Gone is the simple love song formula, the straightforward yet ingenious reggae adaptation, the attempt to look like schoolkids on holiday. 'Ghost in the Machine' presents the Police as responsible adults concerned about the future of the human race and intent on playing music that satisfies themselves if that means no hit singles, so be it. It's a risky but worthwhile strategy.

Another rehash of their pop-reggae fusion would have seemed hackneyed, particularly if the band no longer had its hearts in it. Drummer Stewart Copeland writes eloquently about his dissatisfaction with fame 'n the beautiful ballad 'Darkness' "Instead of worrying about my clothes / could be someone that nobody knows." 'Ghost in the Machine' is partially a concept album based on a book of the same name by Arthur Koestler. The book, which had a profound effect on Sting, is a critical attack on Behaviorist psychology, which Koestler maintains is not the panacea it claims to be but an insidious reduction of human beings to machine status.

Sting has used Koestler's Ideas not to build a story line as in conventional concept albums, but as generalized inspiration for several songs on the record. 'Spirits in the Material World', 'Demolition Man', 'Too Much Information', 'Rehumanize Yourself', "One World (Not Three)' and 'Omegaman'. Those who prefer the less conceptual side of Sting's writing will enjoy 'Every little Thing She Does' and 'Hungry for You'. 'Invisible Sun', a bleak and evocative soundscape based on Sting's impressions of the turmoil in Northern Ireland, has already raised a furore in England, where it was banned. It's a good example of the more complex songwriting structures the Police are now presenting, but the album's musical highpoint is the rocking 'Demolition Man', which kicks hard and features Andy Summers's best recorded guitar work to date.

Review from Record Mirror by Robin Smith

Chapter Four in their continuing book of fame, finds the Police bolder and confidently going where they've only got their big toes wet before. Of course they could have rerun 'Zenyatta Mondatta' in a different package and the little girls wouldn't have cared a bit. 'Ghost In The Machine' (wot a title) proves that they've sat down and thought about where to go next. Sure, they'll always have that definitive snap, crackle and pop, but on this album there's an overall sense of dedication and quality. In my humble opinion, this is the best thing they've ever done. You see, with the other epics I always used to get fed up about the end of side one, as Copeland soft show shuffled and Sting wrapped his tonsils around another abrasive song. But this album has more variety than the menu in a Bangkok brothel. In particular, Sting's voice has taken on a new depth and fresh maturity.

The opening song, 'Spirits In The Material World', may have what sounds like a dumb title, but the song is a dream of close harmonies and nicely understated drums. It contains the first of several political observations and although I could argue with them over these for hours, suffice it to say that the Police sound convincing when they could have easily sounded jaded. 'Every Little Things She Does' is the welcome break between such headiness. A romantic song deft and tender, which starts quietly enough before breaking into mardi gras. Following smartly is the controversial 'Invisible Sun', wonderfully constructed and for me it has the same atmosphere as Bowie's 'Space Oddity'. 'Hungry For You; heads up the street with a bouncing stride and Sting sings in French so I don't know what the hell it's all about - but it provides an enervating insert before more tales of modern life paranoia on 'Demolition Man', aggressively and effectively delivered.

Side two opens with archetypal Police on 'Too Much Information' with chants a go go and the most heavyweight political references so far with comment on the National Front. 'One World Not Three' is dat old White Man's reggae and the next choice for a safe single. Maybe there's even the old Marley influence creeping in there from somewhere. Meanwhile 'Omega Man' is heavy on cosmic strip colour and brashness. Written by Summers it has a fine slant on life reflecting the potential of individuals when best by adversity. 'Secret Journey' is a piece of latter day psychedelia as Sting still with the taste of India in his mouth rattles on about mystical fulfilment. "You will see the light in the darkness".

Honestly this doesn't sound at all stupid within the context of the song. For me through, the best track is the last cut 'Darkness'. It's penned by Copeland and features his working overtime on something supremely atmospheric for want of a better term. Based around a gradually developing theme that creeps up from behind, it has some stunning moments of drama and tension. A track to play after a long hard day and you just feel like lying down and snivelling all over the place. And there you have it. An immensely satisfying album that should vex more than a few Police critics. Girls there's still plenty to scream at, but more importantly this is thoughtful pop for now people.

Review from Smash Hits by Mark Ellen

A fact: The Police make dazzling singles and patchy albums, and this one is no exception. It is, however, as safe an investment as 'Reggatta' and (thankfully) streets ahead of the fearful 'Zenyatta'. Aside from four old-style fillers (plaintive vocal against hectic reggae thrash), the shift is toward a richly textured, synthesised sound coupled with more considered and demanding lyrics. Some in this vein, like 'Spirits In The Material World', are as good as anything Sting's ever written. In short, they've "moved on", matured. Borrow a copy and see if you want to follow. (6 out of 10).

Review from Event by Frances Lass

To the more cynically-inclined, the news that the Copeland Corporation is now pumping politics into their pop/reggae pieces will come as no dropped-jaw revelation. Concern over Northern Ireland, the National Front, and Third World co-operation will be seen as merely a ploy to win back the dwindling British contingent in a bid for credibility. After all, the American single is the typical swing-Sting beauty 'Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic' whereas the British offering 'Invisible Sun' is a wash of swirling, dream-daze sound around which Sting weaves a lament for Northern Irish youth. But since the sentiments are worthy, if not mind-boggling in their radicalism and since the songs are prime stock, why carp? I'd rather they came out on the side of sanity than not at all, given their huge popularity. Branching into mean, moody and mystic music whose content reflects the pseudo-psychology of the Koestler-borrowed title, the balance between the great singles and obvious poly-fillers is weighted, for a change, in the former's favour. An album with heart, and soul of solid gold.

Review from Melody Maker by Paul Colbert

For a while there it was worrying. For a while it looked as if the Police had made themselves a jail of white reggae; barred the windows with blond hair and bleached white vocals and settled in the Outlandos de Regatta Mondatta for umpteen albums to come. They quietly admitted they'd been tired; took people aside and reckoned 'Zenyatta' had sounded fine but could have been better, should have been brighter; there were tours, interruptions... And we said, well 'Don't Stand So Close' was great and 'De Doo, da dum...' or whatever, and thanks for the meal but maybe next time we could go to a different restaurant. In the meanwhile where was the key to this place. They didn't bother looking. This is a break-out. Quite probably the best record they've made and a better advert for a holiday than a topless beach at Nice.

They've refreshed, back on top and sprinting, not walking, on the moon. The Police needed a rest, took it and 'Ghost In The Machine' is the result, a tougher record than ever before, songs frequently pared to one unrelenting riff, early reggae flavours retained, but tainted by an extra touch of funk, an additional dollop of rock'n'roll. Sting today has greater confidence as a political and social commentator; he's no more certain that conditions will or can change but is intent on arguing them. The culture shock of touring India and points wider of the soft west brought a snap reaction on 'Zenyatta'. Brutalised by the insult of mass poverty they hit out anywhere as on 'Driven To Tears'. A year is only just long enough for those experiences to sink in, seep through, for useless rage to become focused anger and for "why does it happen" to reform as "why doesn't it stop". The songs are of conditions rather than events, an approach wrongly raising conclusions that the Police are soft option snipers firing from a position of protected luxury.

There is no wispy conviction within 'One World's simple plea for unity. As the purest reggae track in evidence it has the simplest purpose. 'Too Much Information' sees the brainwaves jammed by outside broadcasts and images thrust at us daily so works against a busy, runabout funk background. Thank Andy Summers for giving the beat a stout clip round the ear. The most obvious sound addition is saxophone, smartly tooted by Sting and invariably arranged a barking backline. Anybody around here heard the word Salsa? Well, no percussion or swirly skirts but the carnival jubilance finds its way onto 'Every Little Things She Does Is Magic'. It's one more musical corner into which the Police lamp flicks an unembarrassed blue glow. Apart from Sting's eight contributions, 'Ghost In The Machine' carries two of the riveting efforts Andy Summers and Stewart Copeland have penned and put to vinyl.

At the back end of side two they help make up a final ten minutes which scales Himalayan heights that early stuff can be wiped off an over activated imagination. By the end of it the Police are no closer to a solution for the global malaise. What they have done is put the strangely disturbing 'Invisible Sun' - incidentally the least obvious single of the 11 tracks and the gloomiest - into perspective. There is a message of hope and at least an inner answer to the equation. It finds a partner in the music's faster beating heart and an echo in the record's highest moment 'Secret Journey'... "You will see light in the darkness, you will make some sense of it, when you make that secret journey, you will find this love you miss."

Review from the Courier-News

After three highly-successful albums, the Police's reggae power-trio formula, although distinctive, was beginning to get cramped in its narrow confines. After all, how much can you do with a spare guitar, bass and drums and no overdubs in a reggae setting? The classy musical interplay had reached its limits. Well, it turns out that despite their massive sales, the band itself was growing weary of the sound and decided to take a few risks. As everyone knows by now, the gamble has paid off handsomely in the commercial marketplace, as 'Ghost in the Machine' sits comfortably in the top three of Billboard's LPs and Tapes chart. But it's also the Police's best album since their debut. The stark instrumentation has been spiced with a much denser sound through the addition of synthesizers, keyboards and saxophones as well as multi-tracked guitars.

In fact, the change is so complete, the synthesizers and saxes so prominent, that in all of the first side, only one selection ('Invisible Sun') doesn't feature one new instrument or another. Yet the album is firmly rooted in the Police's familiar territory of heavy bass-leading reggae-rock, the beats, while varying, are still original, hovering in the usually unexplored territory between reggae's skanking and rock's backbeat. And the added instruments enhance without intruding. In fact, 'Spirits In the Material World' and 'Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic', which open the album, are two of the best songs the Police have ever recorded. They indicate a wholly satisfying growth for the band and a new direction that reaps several rewards. There's still the annoying tendency to play each song (and riff) too long, especially in 'Demolition Man', which has almost all of the two lines. And the four songs that close Side Two are mostly throwaways.

Still, the six good tracks indicate that the fears that the Police would strip-mine their original sound until our ears were exhausted were unfounded. The only question is how the keyboard songs will be performed in concert. All of the instruments on 'Ghost In The Machine' were played by members of the band (including the overdubbed saxes, handled by Sting, a veteran on the horn for all of six months). But in a concert at Liberty Bell Raceway in Philadelphia at the end of the summer, the Police only previewed the songs that featured horns, played by Sting. It may be quite a different line-up the next time around.

Review from New Musical Express by Charles Shaar Murray

O Sting, where is thy depth? And whoever suggested that it was necessary or desirable to plumb it? The Police have run a fair old racket since 1977, when their collective stock was so low that the idea of The Police ever becoming massively popular was only fractionally less ludicrous than the notion that Adam And The Ants could do likewise. Through deafening storms of approbation in every country in the world where Coca0Cola is sold, three well-padded albums and enough decent singles to fill most of one side of a greatest hits album, Sting - The Most Beautiful Man In The World - steps forward to answer your question 'Who's your favourite philosopher?' Well, Lynn Hanna gave the game away last week, and the answer must come as a one hell of a shock to the Watsonian Behaviourists in the Police's audience. One imagines a contest somewhat akin to a cross between the Deputy Leadership and the Oscars: Bette Midler rips open an envelope and announces, "The winner is... Arthur Koestler!" as B.F. Skinner, lips trembling, complexion ashen, does his best to applaud like a good loser should while choking on the fact that the new Police album will not be entitled 'Beyond Freedom And Dignity'.

To support the weight of their current subject-matter, The Police have come up with A New Sound: they've ditched the sharp, cool interlocking fragments of texture and rhythm with which they pioneered New Wave in America and created a sonic blancmange involving hundreds of guitar-synthed, effects-ridden Andy Summers overdubs, a lot of saxophones and several harmonising Stings. They now sound like a cross between The Bee Gees and a reggaefied Yes which I'm sure everybody will agree is one hell of an advance. Only Stewart Copeland's clattering, bustling drums - as audaciously busy and showy as ever - hew to the original blueprint, and Copeland is consistently the most interesting player throughout. The album's best moment comes halfway through the second side with 'One World', a swaggering upful call for unity which almost certainly meets with Miles Copeland’s full approval. Even there, Summers guitar sound is muffled and spongy, but the song's feel and sentiment carry a genuine warmth which is unambiguously appealing. Its worst arrives at the end of the first side: The Police unveil their version of 'Demolition Man', the song that Sting wrote for Grace Jones. This rendition of the song pretty much is a 'walking disaster': Summers plays an extended Heavy Metal solo all the way through the song, and well. I thought my razor was dull until I heard the bass line.

Everywhere else is blancmange (maybe a better title for the album would have been 'Blancmango De Trop', which would have at least preserved conceptual continuity with their first three efforts): whether Sting's being "sexual" on 'Hungry For You', metaphysical on 'Spirits In The Material World' or concerned and aware on 'Invisible Sun', he and his colleagues combine a woolly sound with woolly thinking to minimum effect. Even when they briefly return (via a song for which Stewart Copeland wrote the music) to the punky-trash vein which they mined before the Big Skank hit them, 'Rehumanise Yourself' - the album's second-best track, as it happens - is till weighed down by too much paraphernalia. It's all good humanistic stuff and if rock bands are going to push their favourite philosophers I'd rather take a reggae-ish pop band promoting Arthur Koestler over a pomp(ous)-HM group pimping for Ayn Rand any day of the decade. The fact remains that - as far as this particular listener is concerned - 'The Ghost In The Machine is AMAAAAAAAAAZINGLY DULL.

Sting is obviously a decent, intelligent chap and if we were debating politics and philosophy I'd probably find large areas of agreement with him, but dull music with worthy sentiments attached is, ultimately, no more rewarding an aesthetic experience than dull music with foul sentiments. Koestler's book is available in a Picador edition for considerably less than the cost of The Police's album.

Review from Billboard magazine

Their fourth album marks subtle but ultimately potent shifts in style for the platinum trio, until now playing their reggae inflections and the imaginative interplay of rhythm section and Andy Summer's atmospheric guitar effects as signatures. New here is a more forthright pop verve, previewed on the set's first single. 'Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic', which reveals vocalist/writer Sting's willingness to drop his stylized Trenchtown accent when the material dictates it. Other added twists include the addition of synthesizer and keyboard textures that bring a new sweep to the playing. Still, the band's determination to balance romantic pop conventions with social consciousness remains very much in evidence. In short, smart, stylish and infectious modern pop of the first order. Best cuts: 'Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic', 'Spirits In The Material World', 'Invisible Sun', 'Hungry For You', 'Too Much Information', 'One World'.

Review from The Washington Post by Boo Browning

"Turn on my VCR / Same one I've had for years / James Brown, the 'TAMI Show' / Same tape I've had for years" - The Police, Zenyatta Mondatta Listening to the Police's new album, 'Ghost in the Machine', you half expect Mr. Dynamite himself to come snake-legging out of the woodwork, sweat spilling from his six-inch pompadour to his satin jumpsuit emblazoned "SEX." The sensation is partly the result of bassist Sting's cheesy, sleazy sax riffing - pure adolescent horniness (he only picked up the instrument eight months ago). But it takes more than drive and swagger to plumb the bawdy soul of rock and roll, and 'Ghost' manipulates the slippery essence of the form's mystery and moods with easy energy. Produced by the Police and Hugh Padgham, the record has so much echo it seems to have been made in the bowels of an empty parking garage. But the way the sound has of enveloping its listener has a certain intimate appeal, something akin to being the only attendant at a concert. There is constant movement throughout 'Ghost'.

Floating political and sexual themes sweep around and through the songs in a subliminal cyclone of word association. Both music and lyrics allude and allude again, but seldom to their most obvious referents. Knife-clean synthesizer rhythms open 'Spirits in the Material World', and the band cuts straight to the core of the lyrics in the opening lines: "There's no political solution / To our troubled evolution." Unlike George Harrison's 'Living in the Material World' - essentially a lament - the tune's antipolitics suggest there's freedom in the acceptance of physical mortality, an idea more firmly conveyed when drummer Stewart Copeland snaps the chorus to life. 'Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic' sparkles with bright, calliope-like poppishness; its lyrics bring to mind the optimistic romanticism of the Hollies' 'Bus Stop'. Repeated listening, however, reveals it to be the album's most specious composition: this year's 'De Do Do Do, De Da Da Da'. The pop feeling continues to carry Side A with 'Invisible Sun', a sociological discourse with a touch of early Traffic, and 'Hungry for You', an interesting bit of bilingual horseplay set against Sting's overdubbed sax and Copeland's funky percussion. Either my French is on a hopeless downward spiral, or this song is danceable romantic vampirism.

'Demolition Man' ends the side, a steamroller of a tune that could well be subtitled "Qaddafi's Theme." Sting's "nya nya" sax backdrop, Andy Summers' nasty guitar cackles and the ornery syncopation of the chorus give the lyrics a mean-spirited punch; there's even a false ending for good measure. 'Too Much Information', opening Side B, is typical Police sociology, along the lines of 'De Do Do Do' and 'When the World Is Running Down', but it's about here that the deus ex machina hinted at on 'Invisible Sun' begins to come into focus. 'Rehumanize Yourself', which follows, is clearly the message at work on 'Ghost'. The best lyrics are unprintable, but they're also the best lines on the album. Then comes the musical centerpiece, 'One World (Not Three)'. A spunky combination of rock and rub-a-dub, the song has a knee-dipping sound along the lines of African pop singer Fela Anikulapo Kuti, with the greasy, delayed-timing sax chorus of vintage James Brown. The theme that "one world is enough for all of us" is idealistic, almost banally so, but it gains authority from the global reach of the music. It's a bit downhill from 'One World', though the slope is nearly imperceptible. 'Omegaman' is the flip side, ideologically, of 'Demolition Man'. 'Secret Journey' exhorts us once again to look to the spirit and rehumanize.

I'm wary of a supergroup that confines the bulk of its concert tours to the Third World for the sake of humanism while giving frank indications of a healthy capitalistic appetite. But how to argue with a group that offers sexy, politically charged, accessible pop, whose music inflames where their lyrics miss the spark, and vice versa, whose style looks fearlessly ahead and still keeps moving That, after all, is what we used to call rock and roll.

Review from Flexipop

When you can't go up you can only go down. Don't panic just change the formula. Abandon feeble French title, cool, sparse rhythms and Sting's wail of sound. Bring on the sax, overdubs, special effects and soft vocal harmonies. There, that should cop a few more awards in this year's pop polls. Wonder if they'll like it? Still a formidable force to be reckoned with. Different and daring but this is no cop cock-up. Nothing to get blue about boys. But where to next?

Review from The Sydney Morning Herald by Susan Molloy

The Police have turned out a disappointment. 'Ghost In The Machine' is occasionally promising but more so a sad reminder that some bands have only a limited lifespan before they flounder without sharp musical direction. Never mind, the rewards are pleasant - that poppy little number, 'Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic', is getting high rotation airplay on 2SM and 2UW, so it does pay to leave behind 'Zenyatta Mondatta' and go for 'Ghost'. The best track is 'Invisible Sun' - serious, heavy, menacing, despairing. Straight after this, The Police launch into a messy 'Hungry For You', with Sting's voice almost inaudible under a cacophony of extraneous material which I think is music. And then they try to do Grace Jones's 'Demolition Man'.

Review from The Face by Giovanni Dadamo

One extraordinarily effective way of not enjoying the new Police LP is having to sit down and write about it. Can you imagine a more irritating exercise than striving, from a sedentary position, to produce something that even pretends to be articulate reaction to an artefact which absolutely insists that you leap up and down... Let's try it anyway. First the facts: it's the group's fourth long-player, has eleven tracks, and was recorded at AIR studios, Montserrat, with the exception of one cut 'Every Little Things She Does Is Magic', which came out of Le Studio in Quebec. This last, featuring keyboards from Jean Roussel (the LP's only case of outside musical intervention) is the current Police 45 everywhere in the world bar England, which of course, has the sublime 'Invisible Sun'.

Nothing about 'Ghost In The Machine' convinces me that The Police are anything but a great singles' (vinyl or sexual) band. As a pop LP it's so-so, its magic moments (the two songs already mentioned, Copeland and Sting's 'Rehumanise Yourself', 'Secret Journey' and the irresistibly crass 'Too Much Information') are counterbalanced by an equal number of styrofoam cushions. This is nothing new. This is what one might reasonably have expected after four years in the big saddle. Sting said recently that reading Arthur Koestler's book "Ghost In The Machine" will help to make the album's lyrics clear: "The thoughts of the songs are amplified in the book," says Sting. With all due respects, this is a bit like saying 'Woolly Bully' will take on mind-expanding significance if one spends a year on an Australian sheep farm. In point of fact, the lyrics this time out are more than a little short on quotable content, leaning heavily towards the least seriously digestible end of the late-Sixties peace and love spectrum. 'Spirits In The Material World' has George Harrison's address written on it in indelible ink; Lennon's is all over the simplistic 'One World (Not Three), and so on. I doubt if reading Koestler's book will shed much light on exactly why it's "got to be an invisible sun" either. But who cares? The song's a brilliant piece of pop filigree, and its central sentiments are, after all, on the right side of the barricades.

The same is true of 'Rehumanise Yourself', which matches terrific dance-power in the rhythm section to a verbal I.Q. of around minus five, placing "National Front" alongside "runt" and its other obvious rhyme (although I can think of a few Feminist acquaintances who won't feel quite so friendly at this breakage of The Brand New Big Taboo). On the vitamin deficiency side: an excess of wishy-washy keyboards posing, along with some better infusions of untutored Sting sax and some of the most audible Andy Summers guitar yet to grace a Police album, as musical development. 'Demolition Man' is simply atrocious compared to the Grace Jones version, and the French 'Z'-level vocalising of 'J'Aurais Toujours Faim De Toi (Hungry For You)' will, I wager, have them snorting into their Pernods across the Manche in much the same way that our German cousins slapped their lederhosen in hilarious disbelief at Bowie’s efforts with 'Helden'.

'Ghost In The Machine' is about 50/50 fragile fun and trite tedium, like all Snackpot pop: easily assimilated and, I shouldn't wonder, just as easily forgotten except where, as on previous long-players, The Police preserve their by now traditional ability to provide us with two or three minutes of noise that is truly (forgive me)... arresting.

Review from Chart Songwords

The long lay off between albums seems to have really paid off - it's been a year since the somewhat unfortunate 'Zenyatta Mondatta', which wasn't so much an album as a couple of singles and a lot of filler, whereas this is probably the best Police LP so far. The current single is here of course, with their last smash 'Invisible Sun' plus we think there's a few more likely hits including 'Hungry For You', which Monsieur Sting sings in French! As you've no doubt heard, he also plays saxophone on some tracks. There's a couple of other potential singles here too, like 'Demolition Man', which has already been recorded by Grace Jones, the frantic 'Dehumanise Yourself' (sic) and 'Secret Journey', which is perhaps the best cut on the album. Rating: *****

Review from Creem magazine by Mitchell Cohen

Garry Ahrenberg couldn't get in to the Police, an aesthetic predilection that caused him no small amount of derisive peer pressure. When his buddies - and, worse, Darla Frakiss, the girl who distracted him almost to the point of swooning in Trig 304 - piled into Jim's van and hightailed it to Philadelphia for the outdoor Police show last summer, Garry stayed behind in Dover, New Jersey "I don't see trios in stadiums," he proclaimed "Your loss," Jim shouted, as Darla squeezed into the seat next to him, loopy from the batch or pre trip margaritas "Wait," Garry muttered to himself as he watched Hill Street Blues, "next thing you know - the Police'll cut a Christmas album with Rupert Holmes: 'Pinata Colado'. Come October. the gang all rushed to buy 'Ghost In The Machine' (well, Kirk Chatsworth rushed to buy it everyone else rushed to buy Maxell blank cassettes the artwork sucked anyway, and there was no necessary info on the cover or the sleeve). Garry withheld judgement.

He liked 'Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic' fine, but then again he'd also liked 'Message In A Bottle' and 'De Do Do Do' (especially in Spanish, but even more by the guy on SCTV) yet found the respective albums otherwise tedious. Soon the sound of the new Police LP was wafting through the schoolyard, blasting from the Discovery record store at the mini-mall, a fixture at weekend sleaze blasts. "I'm so tired of the omega-man," Sting sang. Garry was singularly unimpressed "You will see light in the darkness," Sting sang. "Lasarium music," Garry thought. "Too ambitious, to simple-minded. Not unpeppy, though I'll give them that." One lunch period around Columbus Day - the school chef made a Spanish-Italian Special, a pizzarito - Jim, with a concerned look on his face, sidled up to Garry. "When're you going to get cool, pal? Been bad-mouthing the Police again." "Cool?" Garry sputtered. "Cool? Hey, I'm not into one-upmanship but when my cousin Charles sent me the 'Can't Stand Losing You' single from London, you turkeys called it 'reggae-punk garbage' A few months later, you were 'Raahxann'ing allover the place. True or false?" "Well, true, I suppose, but -" "Nothing. Look, like whomever you like, all right. But you have to admit that this 'Ghost In The Machine' thing is as lame as Grandpappy Amos.

The Police get pedantic 'Spirit In The Material World'? 'Darkness'? 'Invisible Man'? 'Secret Journey'? What is this? Hawkwind? Snoozarama city, pal." "So why is WBDR on it so heavy?" "Brain Damage Radio. Doesn't that tell you something? They fit right in there, right alongside Stevie Nicks, Journey and Genesis. What can I say? It leaves me cold. Sounds impersonal. Let's drop it." "Looky there," Jim said, and Garry's head swiveled to catch Darla bopping in the aisle. Walkman II riding on the succulent slope of her hip, headphones resting on her sleek black hair. "Go talk to her, Garry. Tell her you want to raise her rock consciousness. Tell her she's dancing to the wrong beat." Jim got up. "I'm going to the vendomat. Wanna cupcake?" "Funny guy. This year, she's mine. Watch." Garry brushed the crumbs from his denim jacket and walked over to Darla's wall. "Hi," he managed to eek out. "Hi." "J'aurais toujours faim de tois." "What's that?" "That means, 'I am always hungry for you.' It's from the Police album. You know. Great track. I thought all their early albums were pretty much out there, but this one's really melodic and, um -" "Progressive." "Progressive, that's it. Hey did you hear the b-side of the single? It isn't on the album, and I happen to have a copy at home, and I was kind of thinking, well..."